Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

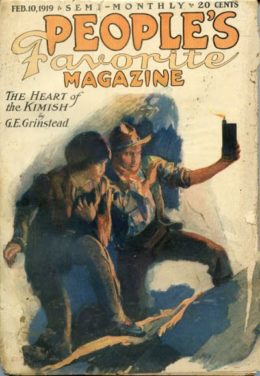

Today we’re looking at Francis Stevens’s (a.k.a. Gertrude Barrows Bennett’s) “Unseen – Unfeared,” first published in February 10, 1919 issue of People’s Favorite Magazine. You can read it more recently in Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s The Weird anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“My eyes fixed themselves, fascinated, on something that moved by the old man’s feet. It writhed there on the floor like a huge, repulsive starfish, an immense, armed, legged thing, that twisted convulsively.”

Summary

Narrator Blaisdell dines with detective Jenkins in a low-rent Italian restaurant near South Street. Jenkins chats about old Doc Holt, recently implicated in a poisoning murder. Only reason Holt was under suspicion was he lives amongst superstitious people, who swear he sells love charms openly and poisons secretly.

Before Blaisdell can learn more, Jenkins leaves him to wander alone through a neighborhood that usually fascinates him—its shabby shops and diverse crowds contrast so strongly with the rest of the city. Tonight, however, the place repulses him. All these Italians, Jews and Negroes, unkempt and unhygienic! To think they are all humans, and he’s human, too—somehow Blaisdell doesn’t like that idea. Normally he sympathizes with poverty and doesn’t shrink from its touch, as he does now from the brush of “an old-clothes man, a gray-bearded Hebrew, [toiling] past with his barrow.”

He senses evil, unclean things to be avoided, and he soon feels physically ill. Sure, he’s a naturally sensitive type, but he won’t give in to his imaginative temperament. If he runs now, he’ll never be able to come to South Street again. So he keeps roaming, trying to collect himself. A banner finally catches his eye. It proclaims: “SEE THE GREAT UNSEEN! FREE TO ALL!”

Blaisdell’s drawn to whatever the banner advertises, though he simultaneously experiences greater fear than he ever knew possible. He forces himself up the steps of the old residence. A party of Italians passes. One young man stares at him, and in his eyes Blaisdell sees “pure, malicious cruelty, naked and unashamed.” Trembling, he enters a malodorous hallway, more rundown rooming house than public space. At least his unreasoning terror has ebbed, and now a well-dressed old man steps into the hall to invite him to view the “Great Unseen.”

The room housing the Unseen is neither museum nor lecture hall but laboratory, with the usual glassware, bookcases, an iron sink and an odd camera on a corner table. The old man orders Blaisdell to sit, then launches into a monologue on the color photography of micro-organisms. But Blaisdell’s sourceless terror has returned, and he pays little attention to the minutiae of which colors of tissue paper must be interposed between darkroom lamp and plate to prevent ruinous fog in the final product. That is, until the old man mentions a sheet of opalescent membrane, obtained serendipitously from a pharmacy. It was wrapped around a bundle of herbs from South America, the clerk said, and he had no more. That makes it all the more precious, as it has proven the key to—well, to what Blaisdell will soon see for himself.

But first, the climax of the monologue! There are beings intangible to our physical senses, though felt by our spirits. But when light passes through the opalescent membrane, its refractive effect in breaking up actinic rays etc. etc. will allow Blaisdell to see with his fleshly eyes what was formerly invisible! Have no fear! (That’s an order.)

The old man turns on his developing lamp, which gives forth green light. Then he inserts his opalescent membrane. The light changes to grayish green and turns the room into “a livid, ghastly chamber, filled with—overcrawled by—what?” Well, there’s a huge, starfish-like thing that crawls up the old man’s legs. Yard-long centipedish things. Furry spiderish things lurking in shadows. Sausage-shaped translucent floating horrors. Things with mask-like human faces too horrible to write of. “Fear nothing!” the old man cries. “Among such as these do you move every hour of the day and night.” And the true horror is that while God made the cosmos and all living things from the ether, man has made these creatures. He might have fashioned blessed phantoms. Instead he has embodied his evil thoughts, panics, lusts and hates into monsters, everywhere. And look what comes to Blaisdell, its creator, the shape of his own FEAR!

And Blaisdell does see a great Thing coming toward him. Consciousness can bear no more. He faints. When he comes to, he’s alone with the conviction that he did not dream the revelations of the night before. No wonder he flinched from human contact and hated his own humanity—all men are monster-makers. Well, with all the bottles of probable poison in this lab, he can at least get rid of his monster-creating self!

Before Blaisdell can down poison, fortunately, Mark Jenkins arrives to save him from himself. It seems that a cigar Jenkins accidentally gave Blaisdell the night before was one of a poisoned batch that killed young Ralph Peeler. Realizing his error with horror, Jenkins pursued his friend. Luckily that young Italian who stared at Blaisdell didn’t do so out of malice but out of worry at how sick Blaisdell looked. Seeing Blaisdell about to enter old Doc Holt’s house had worried the Italian more, so when he saw Jenkins later he mentioned the sick man on the threshold.

So the white-haired man was Doc Holt? Yes, Jenkins says, or rather, how Blaisdell made him up in his poisoned mind, based on portrait in the lab. (Who keeps a portrait of themselves in their lab? People whose thoughts birth giant starfish, that’s who.) He couldn’t have seen the real Holt, though, because Holt had committed suicide the afternoon before. So nothing else could have been real either–all that nonsense about the special light and the Unseen monsters of our making was just hallucination. Phew!

Much as Blaisdell might like to believe this, he saw Holt in the hall before he could have seen the portrait in the lab. Also, he goes to Holt’s lamp and pulls from it a sheet of opalescent membrane. Should they try it out? Jenkins asks, shaken. No, they should destroy it. Blaisdell refuses to believe in human depravity. If the horrors exist, they must be demonic, and demonology is a study best left alone.

Whatever Jenkins may think about that, he agrees with Blaisdell that doubt is sometimes better than certainty, and that some marvels are better left unproved.

What’s Cyclopean: The desires and emotions of mankind are “daily carnified” as “loathsome horrors.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Narrator’s revulsion at poor immigrants does turn out to be a symptom of something seriously wrong. Casual prejudice, of the “of its time” sort, seems to come more naturally: accusing his friend of being as frank as a “Chinese diplomat” or his friend dismissing the neighborhood residents as merely superstitious.

Mythos Making: Terrible creatures lurk around us, waiting only for the right scientific breakthrough to reveal their unfortunate existence.

Libronomicon: No books this week, though material enough for many research articles if anyone cared to write them.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Holt commits suicide, likely because he can’t bear the revelation of the creatures revealed by his study. Narrator (possibly hallucinating and possibly seeing Holt’s posthumous truth) nearly does the same.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Whenever I write about Lovecraft somewhere other than the Reread, the comment inevitably comes: how dare you try to erase Lovecraft’s legacy? It’s a familiar refrain for anyone who discusses Howie in public. And we stare, and blink, and try to fathom how someone might think we were that bad at legacy erasure. If you want an author forgotten, all you have to do is not talk about them. Take my ducked-head embarrassment at never before having read Gertrude Barrows Bennett, “the woman who invented dark fantasy.” Famed in her time, beloved by Lovecraft himself… but she doesn’t have a subgenre named after her, or a thousand anthologies knowingly following in her footsteps. She’s in print, at least, which is more than most of her contemporaries can say. For any artist (though especially for women), the odds of a legacy are against us. May we be remembered in the Archives.

“Unseen – Unfeared” makes a particularly interesting entry into this series because the opening mirrors a certain sort of Lovecraft story, and not in a way that makes a good first impression. Narrator meanders away from meeting a friend in the poor part of town, and is filled with nameless dread ™ by the malevolent immigrants surrounding him. He’s revolted by the Italians and Jews and Negroes walking by; he shudders when a “gray-bearded Hebrew” brushes against him in the street. He says these reactions are atypical, but it’s hard to credit, and when an Italian man glares with further malevolence my first response is, “Maybe it’s because you’re a bigoted jerk.” For Lovecraft, an immigrant neighborhood was both horror in its own right and just a peachy way to set a mood of alienation and isolation for more cosmic horrors. This seemed like more of the same, earlier and perhaps even inspirational.

But Bennett/Stevens is doing something a bit more clever: narrator’s revulsion against his fellow man really is atypical, and turns out to be the delusional side effect of a poisoned cigar. Or possibly intuitive reaction to deeper and more cosmic horrors hidden within the neighborhood—but those are just delusion too, right? We hope? It’s just a hallucinatory dream—unless it isn’t. But there are some things man wasn’t meant to know, and for once man has the sense to turn back from knowing at the last minute. Not merely out of fear, but out of principle. “I refuse to ever again believe in the depravity of the human race.” Amid the decades of cosmic horror, we find few enough characters with this kind of maturity, willing to decide that their glimpse of terror doesn’t spoil all existence after all.

Many of Lovecraft’s own stories end in that moment of psychological dissolution in the lab: accepting proof that human life is meaningless or malignant, and following that proof to its despairing conclusion. The narrator of “From Beyond” spends his life shuddering at the unseen things that surround humanity, unable to move past that revelation. Thurber can’t cope with simply knowing that ghouls exist. A glimpse of a giant Deep One (with a little help from the aftereffects of World War I) drives the narrator of “Dagon” to The Window.

I’m more of Bennett’s mind. Suppose the universe is vast and indifferent? (It is.) Suppose we really are surrounded by terrors beyond human scale? (We are.) None of that cancels out our obligations to take care of each other, or to hope and act on that hope. Even if the reverse is also true.

Addendum: This is our first read out of Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s The Weird anthology, which has a truly impressive table of contents. If we wanted we could run the next couple of Reread years out of this thing, easily. I suspect that in practice we’ll dip into it frequently for the breadth of its weird fiction coverage, with works in translation from as far back as 1918 and samples from Weird traditions worldwide. There are authors I’ve never heard of, and stories I should have thought of but hadn’t considered properly as weird fiction. I’m looking forward to digging in.

Anne’s Commentary

Anne is suffering from a poisoned cigar, or perhaps bad sushi. At least it’s thematic? At any rate, she’ll catch up with us in the comments when she’s feeling better.

Next week, we give in to temptation and sample from the modern end of The Weird table of contents; join us for Reza Negarestani’s “Dust Enforcer.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.